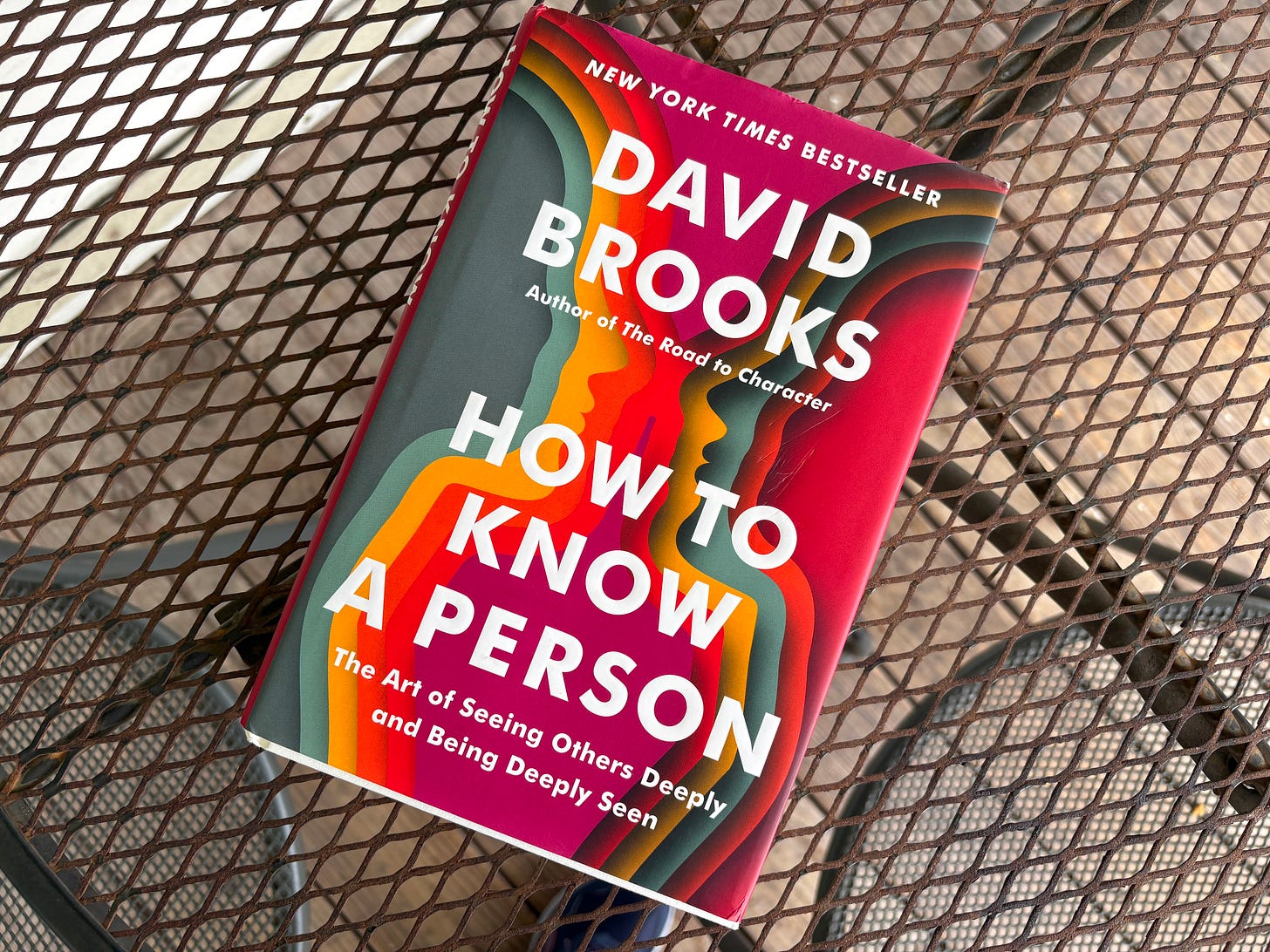

How to Know a Person by David Brooks | Books Everyone Should Read #1

I know that not everyone likes to read, and so when I say that everyone should read a book, I don’t say it lightly. This occasional series will let me try to convince even the most reluctant readers that a certain book is worth reading. If most adults don’t read more than a book a year—let one of these books be that book this year!

Sometimes someone will ask me what I have read recently, and I am not exaggerating when I say my mind goes blank. I have to pull up my Goodreads account and see what the last few books I read were. Of course, once I look at the list I can talk about any of the books I read, but it’s rare that a book lives rent-free in my mind. Occasionally, though, I find a book that feels like it has become a part of me. I have a special shelf for such books, and I do not lend these books out unless it is to someone who I know will return them.

I want to eventually share all these books with you, and the first one is one that occupies a new spot: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen by David Brooks.

The line from this book that buried itself in my psyche almost immediately was this: “The quality of your relationships determines the quality of your life.”

I was already halfway through the book when I read this, and I already loved the book, but as I went about my life in the world, that line kept coming back to me, and I realized how true it was. As I reflected on the good things in my life, I saw how every single thing was because of my relationship with another person. The joy I feel in my home is because of my relationships with my husband and my kids. The emotional stability I feel is because I have people in my life who are safe for me to share things with. If I didn’t have the relationships I have, the quality of my life would, in a word, suck.

Brooks shares the purpose of his book early on. It is “…to help us become more skilled at the art of seeing others and making them feel seen, heard, and understood.” He points out how what most people want and need in order to feel secure is for someone else to respect and accept them. And we can’t do that unless we actually get to know each other.

Early in the book, Brooks divides people into two categories: Diminishers and Illuminators. These two categories describe how a person engages with other people. When I read this chapter, faces immediately popped into my mind in both categories. There are people who walk into a room and suck the life out of it because they are only focused on themselves—these are Diminishers. But then there are the Illuminators, the people who make you feel seen and who turn the light of their attention on you in order to get to know you better. He lists the qualities that help people be one of these kinds of people. Diminishers often struggle with egotism, anxiety, and objectivism, among other things, while Illuminators have developed tenderness, affection, and receptivity.

I think one of the best chapters in the whole book is about how to have a good conversation. I spent years of my life terrified of meeting new people because I felt like I didn’t know how to talk to them. My husband was seemingly born a good conversationalist, and over the years I have learned a lot from him. I used to write down questions to ask people before I went to social situations! In my personal experience, most people do not have this as an innate skill, but it is something you can learn! Some of the tips he gives for good conversations are: treat attention as an on/off switch, be a loud listener, and don’t fear the pause. He also says that you shouldn’t be a topper—in other words, don’t be a Penelope.

Brooks writes several chapters on loneliness and how Covid has changed some of the ways we interact with people. There is also a powerful chapter on his friend Pete who struggled with depression. I wish everyone could read just that chapter, if only to have a better idea of what depression looks like in real life.

Brooks quotes Dennis Proffitt and Drake Baer when they said, “We perceive the world, not as it is, but as it is for us.” What he is trying to communicate is that our view of the world is influenced by so many different things—our personalities, our upbringings, our education, our suffering, and our strengths. The later chapters in the book explore how these different aspects of who we are affect how we see the world and, in turn, impact how we view others.

Brooks also covers “the art of empathy” and gives practices in how to grow in empathy. (One of them is suffering, which I don’t recommend seeking out just for the heck of it.) He helps identify the defenses people use instead of empathy, and knowing these typical defenses can help us see through other people’s reactions.

He covers the “Big Five Traits,” which I was not familiar with. Unlike most other personality tests, these traits have tons of scientific backing. Understanding them and how they might present in someone can really help when you’re in a conversation.

In short, this book is really about how to become a wise person, or, in his language, an Illuminator. Here is how he describes a true Illuminator:

An Illuminator is a blessing to those around him. When he meets others he has a compassionate awareness of human frailty, because he knows the ways we are all frail. He is gracious toward human folly because he’s aware of all the ways we are foolish. He accepts the unavoidability of conflict and greets disagreement with curiosity and respect.

Who wouldn’t want that to describe them? This book helps you understand how to become a person like that.

Ultimately, Brooks says, “Wisdom is a social skill practiced within a relationship or a system of relationships.” If we want to grow into this kind of person, then we have to be in relationships.

The reflection this book prompted in me showed up in a few different conversations I had in the weeks after finishing the book. Here are three little vignettes:

I was in a situation with someone who I’ve spent a little time with but who I didn’t know well. I asked this person where their spouse worked, and the spouse’s job was what many in our area would consider politically and even morally controversial. I felt a tiny little bit of shock, but instead of shutting the conversation down, I put myself in the shoes of this person and this person’s spouse, and I asked what it was like for them to work there. This kept the conversation going and I learned so much about this person and their spouse!

I met someone knew and asked what their job was. The person somewhat off-handedly mentioned another job they did in the evenings, so I asked more questions. After a few minutes we discovered this person went to graduate school at the same place as my husband (and it is a very small school). A new friendship was born mostly because I kept asking questions.

Someone approached me about a conflict that involved our kids as well as someone else’s kids. This other parent is not someone either of us knew well. The onus was on me to reach out to this other parent. At first, I felt really anxious. But in thinking about this book, I thought about how every person just wants to feel respected and seen. I didn’t assume anything and was willing to own what my child had done in the situation. This other parent seemed grateful that I had just spoken up instead of being passive aggressive, and now we are closer friends as a result.

These are just little examples, pulled from my every day life, and I feel like they all happened because of what I had learned from this book.

Another outcome from reading this book was that I felt compelled to start writing a novel.

I’m sorry, what?

I know, friends, I didn’t see it coming, either. But then I read the following quote from the end of the book:

Not long ago I was at a dinner party at which two very good novelists were present. Someone asked how they began the process of writing their novels. Did they start with a character and then build the story around that, or did they start with an idea for a plot and then create characters who operate within the story? They both said they didn’t use either of these approaches. Instead, they said, they started with a relationship. They started with the kernel of an idea about how one sort of person might be in a relationship with another sort of person. They started to imagine how the people in that relationship would be alike and different, what tensions there would be, how the relationship would grow, falter, or flourish. Once they had a sense of that relationship, and how two such characters would bounce off and change each other, then the characters would flesh out in their minds. And then a plot tracing the course of that relationship would become evident.

I had been thinking about the premise for a book for a long time, but I only had one thing: a mother and daughter relationship. I didn’t know if I could get a book out of that, or if it could even be interesting. When I read this paragraph the through-line of the book materialized in my brain. I started thinking about all my favorite fiction books and how the best part about them is the relationships and how the people in the relationships grow and change as a result of the relationships.

Don’t get too excited about the novel—it’s still very much in the womb. But if I ever actually write it, I feel like I’ll have to include David Brooks in the acknowledgements.

I’d love to know if you’ve read this book—and if you haven’t, go read it now! You’ll be a better person if you take the advice in these pages.

I agree, this is such an impactful book! It provides so much food for thought, and I am endlessly fascinated at how different points stand out for different readers (always one of my favorite aspects of books / book club discussions). Thank you for sharing your takeaways here!

I downloaded it last week to listen to and then life happened and I couldn't focus on it (Iykyk), but I plan on listening asap! Thanks for sharing your thoughts and takeaways, and though I don't read much, I would most def read your novel!!! You are an amazing friend and an illuminator to most people. May we all become illuminators and love one another well! Thanks for using your talents to bless us all.